Authoritarian—and not just authoritarian—governments typically see national history as an important way to shore up support for the regime. China is probably the most prominent example of that right now, as Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party reinforce their efforts to teach every Chinese citizen the glories of the party’s history and to conceal the truth about such crimes as the land‐reform campaigns of the early fifties, the Cultural Revolution, the Great Leap Forward, and the Tiananmen Square massacre. But a new book reveals the efforts of unofficial historians to make sure the truth is not lost.

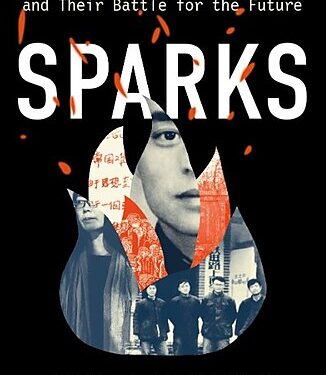

The book by Ian Johnson is Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future. Ian Buruma has a long and informative review in the New Yorker:

Johnson’s underground historians are mostly concerned with unearthing and keeping alive forbidden memories of the past. Official Party history, imposed on China’s population, is also a matter of official forgetting. Many people born in China after 1989 have never heard of the Tiananmen massacre. Many of the young people who lived through the Cultural Revolution, in the nineteen‐sixties and early seventies, would have had limited knowledge of the Great Leap Forward, in the late fifties and early sixties, when Mao’s crackpot schemes for industrial and agricultural transformation caused tens of millions of deaths from starvation. And many of those who starved may not have been fully aware of the land‐reform campaigns of the early fifties, when vast numbers of people were murdered as class enemies, because they owned some land (as Mao’s father did, but that is a fact Party ideologues prefer to keep quiet).

The book’s title comes from a secretly mimeographed magazine, Spark, that began in 1960. It lasted only two issues, “and some of the contributors were executed as ‘counter‐revolutionaries’ after spending years in prison under horrifying conditions.” But it inspired “the writers, the scholars, the poets, and the filmmakers who found the courage to challenge Communist Party propaganda.”

Johnson describes efforts over many decades and also ongoing work today. Of course, “None of this work can be released in China.… But Johnson’s underground historians are mostly concerned with unearthing and keeping alive forbidden memories of the past. Official Party history, imposed on China’s population, is also a matter of official forgetting.”

It’s an inspiring story. And of course China is not the only country trying to craft an official history that may veer far from the truth. The Soviet Union pioneered official history and official forgetting before Mao came to power and before George Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty‐Four. After the fall of the USSR the dissident and human rights activist Vladimir Bukovsky, who late in life was a Cato senior fellow, devoted much of his efforts, along with organizations as Memorial, to exposing the crimes of the Communist Party.

Of course, history is a concern of liberal and democratic countries as well. Shakespeare wrote plays that promoted the claims and the achievement of the Tudor dynasty, which was most pleasing to Queen Elizabeth I. The American Founders believed that the study of history is our best guide to the present and the future. The authors of the Federalist Papers wrote of history as “the oracle of truth” and “the least fallible guide of human opinions.” From their study of history they learned of the ancient rights of Englishmen, the importance of individual virtue in preserving freedom, and the dangers of power and thus the necessity of constraining and dividing it.

History helps us to understand the development of our civilization, including the ideas that shape it. Often the ideas that we now regard as universal principles arose in response to particular circumstances. Magna Carta and similar medieval charters reflect the struggle to constrain the power of kings. From such guarantees of specific liberties, eventually liberty developed. The rights guaranteed in the Bill of Rights reflected particular historical experiences: with religious wars, censorship, confiscation of property, the Star Chamber, and the constant tendency of government to seek more power.

People get much of their understanding of government and policy from history. The way we view the Constitution, slavery, Jim Crow, the industrial revolution, the robber barons, the New Deal, and other historical events shapes our view of the present. And in a liberal society we’re not always going to agree on the lessons or even the facts of history.

Scholars such as Frances Fitzgerald have written about past battles over how to tell the American story. And of course we’re having heated disputes today over how to understand and teach American history.

But for now I want to focus on the courageous efforts of Chinese citizens who have given so much to keep the truth alive. And I’ll also note that we at the Cato Institute have done our very little bit to introduce dissident ideas into China.

During the post‐Mao opening Cato held conferences on liberty, limited government, and free markets in China in 1988,1997, 2000, and 2001. The 1998 conference, featuring Milton Friedman, numerous Chinese scholars, and a Friedman meeting with Premier Zhao Ziyang, was surely the first conference on market liberalism in Chinese history. Papers from the conference were published in both English and Chinese (English title Economic Reform in China), as were papers from the 1997 conference (China in the New Millennium). Several Cato books have been published in China: my Libertarianism: A Primer (later updated as The Libertarian Mind) in 2012, Johan Norberg’s books In Defense of Global Capitalism and Progress, Randal O’Toole’s Gridlock and The Best‐Laid Plans, and just last month the Cato Handbook for Policymakers.

Ian Johnson is telling an important story of heroic Chinese people who for more than 60 years have been making sure historical truth is not lost in a great country.