Adam N. Michel and Dominik Lett

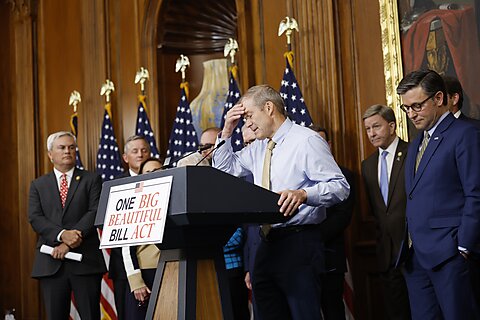

Republicans are talking about another budget reconciliation bill: Reconciliation 2.0. The question is whether Congress should give it a try. The short answer: only if it shrinks the size and scope of the federal government. The first reconciliation package, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), was a mixed bag. Reconciliation 2.0 could fix some of its biggest shortcomings by shrinking the deficit through cutting spending. A well-crafted bill could restore federalism and reverse government policies that raise Americans’ cost of living. But sequels are rarely as good as the original.

The Case Against Reconciliation 2.0

Wall Street Journal columnist Kimberly Strassel lays out a persuasive case for skepticism. She warns that a second reconciliation could quickly become a grab bag of unrelated policies: funding for District of Columbia security, new drug price controls, tax increases on high-income Americans, and watered-down health care reforms. Each of these would expand the worst features of OBBBA, adding complexity, new spending, and more government micromanagement of the economy.

And it doesn’t take much imagination to see how the list could grow. Senator Josh Hawley floated a tariff rebate, reviving the costly COVID-era policy that helped spark the highest inflation in decades. Others may push to extend Biden’s expensive ObamaCare subsidies, expand the child tax credit, provide new funding for farm subsidies, expand foreign aid, or any number of other parochial interests.

The danger is that instead of correcting OBBBA’s shortcomings, Congress doubles down on them.

The Case for Reconciliation 2.0

Matt Dickerson at the Economic Policy Innovation Center makes the opposite case: Reconciliation 2.0 could be a beautiful sequel. His argument is that OBBBA left plenty of good ideas on the cutting room floor. If Republicans can assemble a package focused on meaningful reforms, why not give it a try?

There is something to this. OBBBA succeeded in locking in pro-growth tax reforms and reducing the growth rate of some spending categories, but it left plenty undone. Republicans need a unifying goal for a successful package. We propose an affordability agenda, ending government intervention that drives up the costs of living and pursuing tax changes that protect Americans from reigniting inflation.

On the spending side, Congress should think bigger than OBBBA if it wants to be successful. The law cut spending modestly, but if it is extended, deficits are still projected at $3 trillion annually within a decade. Reconciliation 2.0 must do better, focusing on structural reforms that devolve spending to the states and reduce government intervention.

The government-run health care sector illustrates this problem well. Medicare is the second-largest government program after Social Security and is almost entirely responsible for the federal government’s worsening fiscal outlook. The OBBBA left several commonsense reforms to Medicare on the cutting room floor, such as paying private physicians and hospitals the same rates for the same services (a.k.a. site-neutral payments) and reducing overpayments in the Medicare Advantage program. Adopting these reforms could reduce federal deficits by more than $500 billion while also cutting premiums for Medicare beneficiaries by more than $150 billion. For taxpayers and patients alike, these are win-win, no-brainer reforms for Reconciliation 2.0.

The OBBBA made several modest but positive Medicaid reforms, adding work requirements and curbing states’ use of “provider taxes” to game its financing system. A second bill that put provider tax limits on a glidepath to zero would strengthen the original reforms and save billions more. Reconciliation 2.0 should go further by ending policies that privilege able-bodied, childless adults over the truly needy and by reducing the excess Medicaid dollars flowing to wealthy states (a.k.a. removing the FMAP floor). Either reform could save more than $500 billion over the next decade.

Streamlining the federal bureaucracy by bringing public sector retirement benefits in line with private sector benefits could save $238 billion over the next 10 years. Further savings could be secured by ending costly Biden-era industrial policy subsidies for both chipmakers and energy companies. Slashing these subsidies would strengthen the economy by reducing unnecessary federal interventions and cutting the federal budget deficit by hundreds of billions of dollars.

If the OBBBA is made permanent, the Committee for a Responsible Budget estimates taxes will average 16.8 percent of GDP over the next decade. That is a full half a percentage point below the 50-year federal revenue average. Cutting taxes further requires serious and lasting spending cuts. But there’s still a lot of tax reform that’s left to be done. Closing remaining loopholes, such as the tax subsidy for municipal bonds, corporate deductions for state and local taxes, and a maze of education tax credits, would broaden the tax base and create room to cut rates elsewhere.

Congress can help protect Americans from inflation by indexing capital gains and other parts of the code so that Americans aren’t taxed on inflationary gains. Better yet, it could lower capital gains and dividend tax rates to reduce the distortion of inflation. Trump’s proposed 15 percent corporate income tax rate didn’t make it into the first package, but moving to a globally competitive rate would reinforce OBBBA’s incentives to invest and recommit Congress to letting markets, not Washington, allocate capital investments. Future reform should also make the new manufacturing structures deduction permanent (it is slated to expire after 2028) and extend similar treatment across the economy.

We highlight the latter on the continuum of fundamental reform to modest steps to control spending growth. Congress can and should go much further, block-granting and phasing out most federal welfare spending and dramatically lowering taxes across the board.

Fix or Fiasco?

The case for Reconciliation 2.0 depends entirely on its contents. If it becomes a Christmas tree of new spending and special-interest deals, it will be a fiasco. But if Congress uses the opportunity to deliver real spending reforms, it could be the fiscal course correction the country is still waiting for Congress to deliver.

Sequels often disappoint, but occasionally they surpass the original. The Empire Strikes Back did. Reconciliation 2.0 could too, but only if Congress resists the temptation to repeat OBBBA’s mistakes and instead tackles the hard choices Washington has long dodged.